A few days ago, speaking to a couple friends, I asked them the cliché thing you ask people who do not speak your native language, ‘how do you say ‘hello’ in your mother-tongue?’. My friends are a little over the youth group age, grew up in a setting where they spoke their native language and are both from the same Kenyan tribe. Shock on me, they couldn’t agree on a common phrase that said ‘hello’ in their mother-tongue. We spent another half hour or so discussing the difference in meaning in the various phrases that were presented; when you can say it, to whom you can say it and how you can say it. As you can imagine, this was all very confusing for me. A native speaker of my mother-tongue, ekegusii.

A few weeks ago, the swahili greeting phrase “Shikamoo” sparked controversy on social media when the linguists came to correct all of us on its use. You should only use ‘Shikamoo’ when greeting your elders and NOT your peers or those younger than you! How many of us remember the numerous times our school teachers greeted us with ‘Shikamoo wanafunzi’ on swahili Wednesday? As we have come to learn, different languages have gender, age, location, among other nuances that we only learn on the go.

I grew up in the village, Nyamira, and can speak my mother-tongue very fluently. Both my parents spoke the language at home but my dad, a High School Principal (now retired), preferred that his 8 children communicated in English. As he argued, you will be tested in English and one subject in swahili. You will not be tested in your native language. His house, his rules.

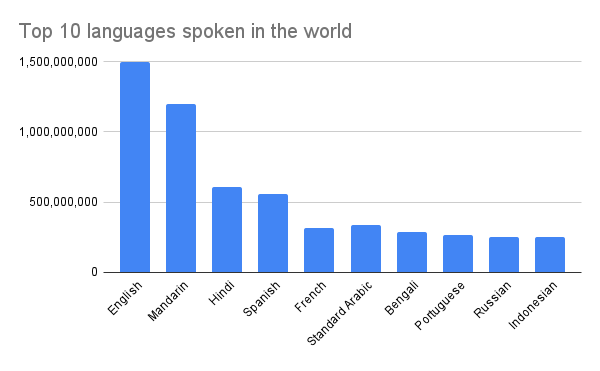

The world is going through an interesting transformation where natural language processing is the big thing running global economies with large language models dominating their use and need for resources – investments, data centres etc. When I was a student of computer science and studying AI, I always thought NLP was the sleepy sibling in the AI family but lo and behold, the nice ones sometimes finish first! LLMs are powered by algorithms and language data that primarily focuses on the ‘large languages’. The smaller you go, the less representation there is.

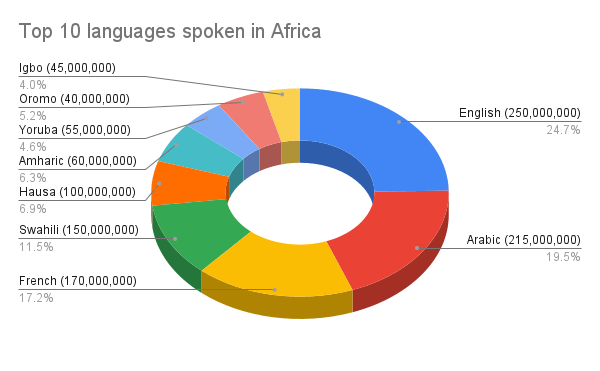

The thing that is common among the top 10 languages spoken in the world is, the young ones of the native countries speak the language and the school text is also in these languages. We have seen global leaders travel around with interpreters and local athletes power through languages that are foreign to them.

I have two children, born and growing up in a city setting. My husband and I do not speak the same native language so naturally our mode of communication is English. Our Kids speak English and one speaks some French as it is offered in school. They both know when Mama is angry because I go back to the basics, ekegusii. But, if we are raising children who cannot speak our native languages, what is the business case for the investment that is going into the various initiatives for localization of AI into African languages?

Source: funmioyatogun.com

There are over 2,000 languages spoken in Africa and my native language – ekegusii – has approximately 2.7 million speakers according to the 2019 KNBS census.

So, what is this post about?

There are multiple initiatives that are doing a lot of good work in documenting and producing data on various African languages. Some of these include Masakhane and KenCorpus. Beyond the archival function of these initiatives, there is a need to scale them to bring on more users that will carry this initiatives forward and make a case for more investment and effort towards mainstreaming local languages. Schools and homes present this opportunity.

Languages carry traditions, culture and community. In the subtle changes in dialect or ascents. In the bold presentation of heaviness of the tongue or clicking of the sounds lies a great opportunity to pass this on to our children and the future generation. The erasure of language means the erasure of communities and their histories. For Africa to be adequately represented in the AI and data space, the efforts need to go beyond our gender, race and age. It needs to go into our languages and the more people who can speak these languages, the more they cannot be ignored.

Mbuya mono!

Leave a comment